The term slangis extremely vague and ambiguous. There are a lot of distinctions of it but none of them is specified exactly. It is presented both as a special vocabulary and as a special language. So, in most of the dictionaries sl. (slang) is used as a convenient stylistic notation for a word or a phrase that cannot be specified more exactly.

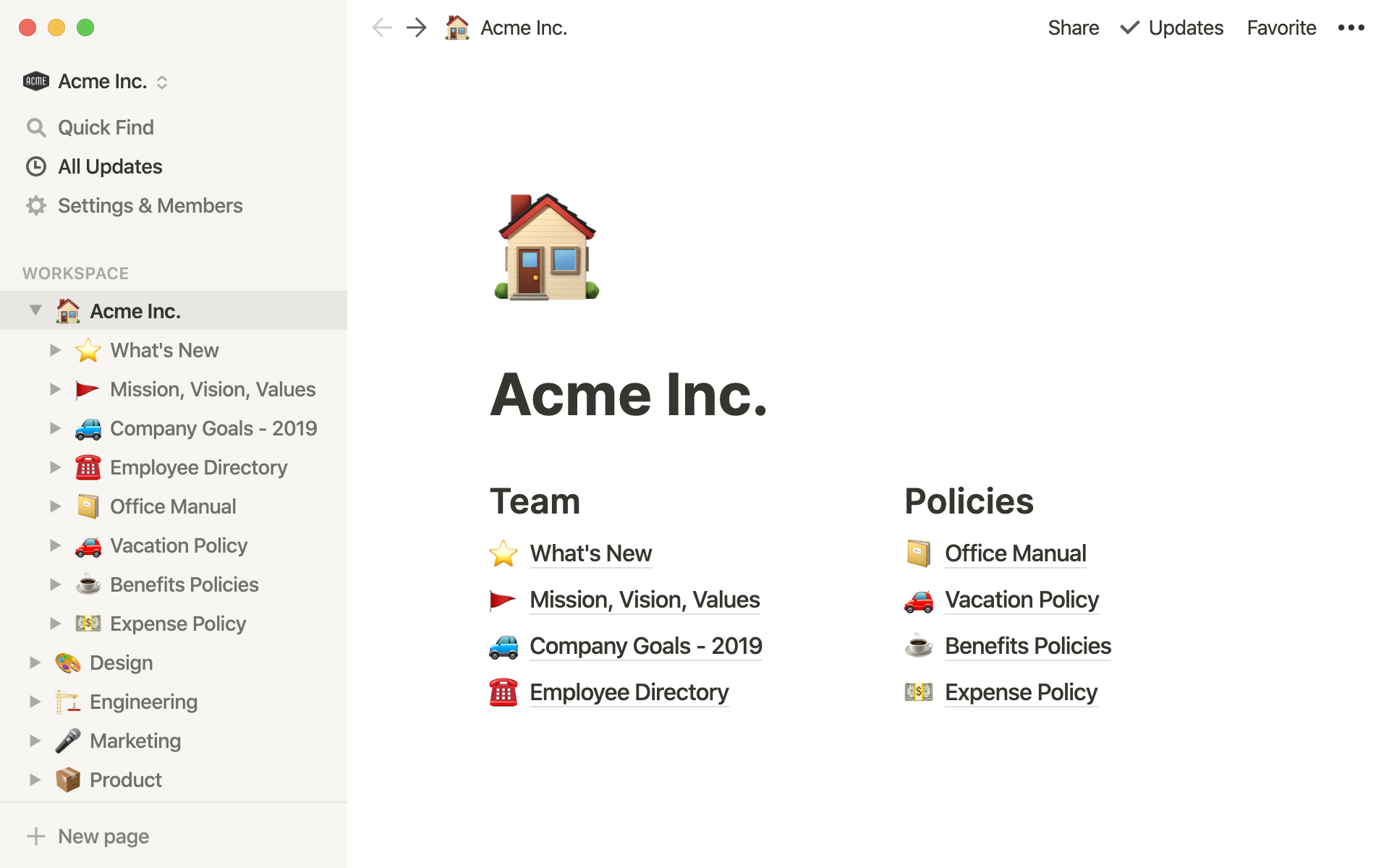

- Sick of fake Notion reviews? Our software experts have spent 357 hours analyzing project management tools. Find out the facts ➤ what makes Notion tick?

- When pandoc is used with -t markdown to create a Markdown document, a YAML metadata block will be produced. Some output formats have a notion of a class.

Jargonis a recognized term for a group of words that exists in almost every language and whose aim is to preserve secrecy within a social group of people. The most well-known jargons in English are: the jargon of thieves, generally known as cant; the jargon of jazz musicians etc.

Some American linguists refer to informal language as slang and reserve the term jargon for the technical vocabularies of various occupations. Some linguists consider slang to be regional, and jargon – social in character.

Notion is the all-in-one workspace. From notes, tasks, wikis, to database, Notion is all you need. Works great for teams and individuals. Available in the browser, iOS, Mac, and Windows.

Professionalisms are the words used in a definite trade, profession or calling by people connected by common interests both at work. Professionalisms are correlated to terms, which are coined to nominate new concepts that appear in the process of technical progress and the development of science.

In this paper we research the language used by hackers – a technical culture that appeared under the influence of computerization. Hackish (see Glossary of Terms) is traditionally the jargon though many linguists distinguish it as slang.

To make a confused situation worse, the line between hackish slang and the vocabulary of technical programming and computer science is fuzzy, and shifts over time. Further, this vocabulary is shared with a wider technical culture of programmers, many of whom are not hackers and do not speak or recognize hackish slang.

Accordingly, we tried to distinguish among three categories:

slang: informal language from mainstream English or non-technical subcultures (bikers, thieves, rock fans etc).

jargon: informal «slangy» language peculiar to or predominantly found among hackers; it is the language hackers use among themselves for social communication, fun, and technical debates.

techspeak: the formal professional technical vocabulary of programming, computer science, electronics, and other fields connected to hacking.

This terminology will be consistently used throughout the remainder of this research project.

The distinction between jargon and techspeak is extremely delicate. A lot of techspeak originated as jargon, and there is a steady continuing uptake of jargon into techspeak. On the other hand, a lot of jargon arises from generalization of techspeak terms (see 2.2.4.).

It is very difficult to research the apparent origin of technical terms, for several reasons. First, many hackish usages have been independently reinvented multiple times, even among the more obscure and intricate neologisms. It often seems that the generative processes underlying hackish jargon formation have an internal logic so powerful as to create substantial parallelism in different languages. Second, the networks tend to propagate innovations so quickly that `first use' is often impossible to trace.

In general, techspeak considers any term that communicates primarily by a denotation well established in textbooks, technical dictionaries, or standards documents.

Hackerdom

'The word hack doesn't really have 69 different meanings', according to MIT hacker Phil Agre.

Hacking might be characterized as `an appropriate application of ingenuity'. An important secondary meaning of hack is `a creative practical joke'.

The «hacker culture», or hackerdom is a loosely networked collection of subcultures that contains some important shared experiences, shared roots, and shared values. It has its own myths, heroes, villains, folk epics, in-jokes, taboos, and dreams. Because hackers as a group are particularly creative people who define themselves partly by rejection of `normal' values and working habits, it has unusually rich and conscious traditions for an intentional culture less than 40 years old.

As usual with slang, the special vocabulary of hackers helps hold their culture together; it helps hackers to recognize each other's places in the community and expresses shared values and experiences. Also as usual, not knowing the slang (or using it inappropriately) defines one as an outsider, a mundane, or (worst of all in hackish vocabulary) possibly even a suit. All human cultures use slang in this threefold way -- as a tool of communication, inclusion, and exclusion.

However, among hackers slang has a subtler aspect, which can be paralleled to the slang of jazz musicians and various kinds of fine artists but hard to detect in most technical or scientific cultures; parts of it are code for shared states of consciousness. There is a big range of altered states and problem-solving mental states basic to high-level hacking. Hacker slang encodes these subtleties in many unobvious ways. For example, there is a distinction between a kluge and an elegant solution, and the differing connotations attached to each. The distinction is not only of engineering significance; it reaches the nature of the generative processes in program design. Hacker slang is unusually rich in implications of this kind, of overtones and undertones that reveal the hackish psychology.

Hackers, as a rule, play with words and are very conscious and inventive in their use of language. Thus, linguistic invention in most subcultures of the modern West is largely an unconscious process. Hackers, by contrast, regard slang formation and use as a game to be played for conscious pleasure. Their inventions thus display an almost unique combination of enjoyment of language-play with the discrimination of educated and powerful intelligence. Further, the electronic media which keeps them together are fluid, `hot' connections, well adapted to both adopting of new slang and the ruthless culling of weak and exclusion of «weak» and old-fashioned words and word combinations. The results of this process give us a uniquely intense and accelerated view of linguistic evolution in action.

Hacker slang also challenges some common linguistic and anthropological assumptions. For example, it has recently become fashionable to speak of `low-context' versus `high-context' communication. Low-context communication is characterized by precision, clarity, and completeness of self-contained utterances. It is typical in cultures, which value logic, objectivity, individualism, and competition. By contrast, high-context communication (elliptical, emotive, nuance-filled, multi-modal, heavily coded) is associated with cultures, which value subjectivity, consensus, cooperation, and tradition. Hackerdom is widely known by extremely low-context interaction with computers and exhibits primarily 'low-context' values, but cultivates an almost absurdly high-context slang style.

Hacker subcultures

The most well-known hacker subcultures are:

Crackers;

Phreakers;

LISPers.

Cracking is the act of breaking into the computer system; what a cracker does. Contrary to widespread myth, this process does not usually involve hackish brilliance, but rather persistence and repetition of tricks that exploit common weaknesses in the security of target systems. Crackers are considered to be mediocre hackers. Use of both these neologisms reflects a strong revulsion against the theft and vandalism perpetrated by cracking rings. It is expected that any real hacker does some playful cracking and knows many of the basic techniques, anyone is expected to have overcome the desire to do so except for urgent, practical reasons (for example, if it’s necessary to break a security in order to do something lively necessary).

Thus, there is a greater difference between hackerdom and crackerdom than most peoplemisled by sensationalistic journalism might think. Crackers tend to gather in small, very secretive groups that have little overlap with the huge, open poly-culture of hackers; though crackers often describe themselves as hackers; hackers, in their turn, consider crackers a lower form of life; they do not respect anyone who breaks into someone else’s computer.

Phreaking is the art and science of cracking the phone network (so as, for example, to make free long-distance calls). By extension, security-cracking is used in any other context (especially, on communications networks). At one time phreaking was a semi-respectable activity among hackers; there was a gentleman's agreement that phreaking as an intellectual game and a form of exploration was normal, but serious theft of services was a taboo. There was significant crossover between the hacker community and the hard-core phone phreaks who ran semi-underground networks of their own. This ethos began to break down in the mid-1980s as wider dissemination of the techniques put them in the hands of less responsible phreaks. Around the same time, changes in the phone network made old-style technical ingenuity less effective as a way of hacking it, so phreaking came to depend more on criminal acts such as stealing phone-card numbers.

LISP (from `LISt Processing language', but mythically from `Lots of Irritating Superfluous Parentheses' is a language based on the ideas of variable-length lists and trees as fundamental data types, and the interpretation of code as data and vice-versa. All LISP functions and programs are expressions that return values; this, together with the high memory utilization of LISPs, gave rise to a famous saying (a periphrasis of Oscar Wilde quote) that 'LISP programmers know the value of everything and the cost of nothing'.

Part II

Jargon Construction

There are some standard methods of jargonification that became established quite early (i.e., before 1970). These include verb doubling, soundalike slang, the `-P' convention, overgeneralization, spoken inarticulations, and anthropomorphization. These methods, as well as the standard comparatives for design quality are covered below.

Of these six, verb doubling, overgeneralization, anthropomorphization, and (especially) spoken inarticulations have become quite general; but soundalike slang is still largely confined to MIT and other large universities, and the `-P' convention is found only where LISPers flourish.

Verb Doubling

A standard construction in English is to double a verb and use it as an exclamation.

E.g. 'Bang, bang!' or 'Quack, quack!»

Most of these are names for noises. Hackers also double verbs as a concise, sometimes sarcastic comment on what the implied subject does. Also, a doubled verb is often used to terminate a conversation, in the process remarking on the current state of affairs or what the speaker intends to do next. Typical examples involve win, lose, hack, flame, (see Glossary of Terms) culture has one *tripling* convention unrelated to this; the names of `joke' topic groups often have a tripled last element. The first and paradigmatic example was alt.swedish.chef.bork.bork.bork.

Other infamous examples have included:

alt.french.captain.borg.borg.borg

alt.wesley.crusher.die.die.die

comp.unix.internals.system.calls.brk.brk.brk

sci.physics.edward.teller.boom.boom.boom

alt.sadistic.dentists.drill.drill.drill

Soundalike Slang

Hackers often make rhymes or puns in order to convert an ordinary word or phrase in order to achieve a humorous effect. It is considered particularly flavorful if the phrase is bent so as to include some other jargon word. For instance, the computer hobbyist magazine 'Dr. Dobb's Journal' is almost always referred to among hackers as `Dr. Frob's Journal' or simply `Dr. Frob's'. Terms of this kind that have been in fairly wide use include names for newspapers

E.g.: Boston Herald - Horrid (or Harried)

Boston Globe - Boston Glob

Houston (or San Francisco) Chronicle - the Crocknicle (or the Comical)

New York Times - New York Slime

However, the following terms are often made up on the spur of the moment. Standard examples include:

IBM 360 - IBM Three-Sickly

Government Property -- Do Not Duplicate (on keys)

ð Government Duplicity -- Do Not Propagate

for historical reasons - for hysterical raisins

Soundalike slang has been compared to the Cockney rhyming slang it has been compared to in the past (see the Glossary of Terms). They are not really similar because Cockney substitutions are opaque whereas hacker punning jargon is intentionally transparent.

The -P convention

The –P convention means turning a word into a question by adding the syllable `P'. It originated from the LISP convention of appending the letter `P' to denote a predicate. The question expects a yes/no answer.

E.g.: 1) At dinnertime:

Question: 'Foodp?'

Answer: 'Yeah, I'm pretty hungry.' or 'T!'

2) Instead of «How are you doing?»:

Question: 'State-of-the-world-P?'

Answer: (Straight) 'I'm about to go home.'

Answer: (Humorous) 'Yes, the world has a state.'

3) On the phone to Florida:

Question: 'State-p Florida?'

Answer: 'Been reading JARGON.TXT again, eh?'

Once, when Bill Gosper, a famous hacker, was at a Chinese restaurant with his friends, he wanted to know whether someone would like to share with him a two-person-sized bowl of soup. His inquiry was: 'Split-p soup?' It is known to be one of the best hacks.

The most frequently used positive reply to a question using Îøèáêà! Çàêëàäêà íå îïðåäåëåíà.) is «T’, which is taken from the LISP terminology and means «true’. Some LISP hackers use `T' and `NIL' (New Implementation of LISP) instead of `Yes' and `No' almost reflexively. This sometimes causes misunderstandings. For example, when a waiter or flight attendant asks whether a hacker wants coffee, he may absently respond `T', meaning that he wants coffee; but of course he will be brought a cup of tea instead.

Generalization

A very conspicuous feature of jargon is the frequency with which techspeak items such as names of program tools, command language primitives, and even assembler codes are applied to contexts outside of computing wherever hackers find amusing analogies to them. One of the best-known examples of generalization is that Unix hackers often grep (see the Glossary of Terms) for things rather than search for them.

Hackers enjoy generalization on the grammatical level as well. They add the wrong endings to various words and them make nouns and verbs, often by extending a standard rule to non-uniform cases (or vice versa).

E.g.: porous - porosity

generous - generosity

Hackers successfully generalize:

mysterious - mysteriosity

ferrous - ferrosity

obvious => obviosity

dubious => dubiosity

Another class of common construction uses the suffix `-itude' to abstract a quality from almost any adjective or noun. This usage arises especially in cases where mainstream English would perform the same abstraction through `-iness' or `-ingness'.

E.g. win => winnitude (a common exclamation)

loss => lossitude

cruft => cruftitude

lame => lameitude

Some hackers cheerfully reverse this transformation. For example, they argue, that the horizontal degree lines on a globe ought to be called `lats' because they measure latitude!

Also, hackers noun verbs.

E.g.: 'I'll mouse it up', 'Hang on while I clipboard it over'.

This is only a slight overgeneralization in modern English that all verbs can be nouned. In hackish, however, it is good form to mark them in some nonstandard way.

E.g.: disgust => disgustitude

hack => hackification

English as a whole is already heading in the direction towards pure-positional grammar like Chinese; hackers are simply a little ahead of the process.

However, hackers avoid the unimaginative verb-making techniques characteristic of marketroids, bean counters, and the Pentagon; a hacker would never, for example, `productize', `prioritize', or `securitize' things. Hackers have a strong aversion to bureaucratic bafflegab and regard those who use it with contempt.

Further, certain kinds of nonstandard plural forms prevail in hacker jargon. Some of these go back quite a ways; the TMRC Dictionary includes an entry which implies that the plural of `mouse' is meeces, and notes that the defined plural of `caboose' is `cabeese'. This latter has apparently been a standard joke among railroad enthusiasts for many years.

On a similarly Anglo-Saxon note, almost anything ending in `x' may form plurals in `-xen'. Even words ending in phonetic /k/ alone are sometimes treated this way.

E.g.: `soxen' for a bunch of socks.

Other funny plurals are `frobbotzim' for the plural of `frobbozz' (see frobnitz) and `Unices' and `Twenices' (rather than `Unixes' and `Twenexes'. But note that `Unixen' and `Twenexen' are never used; it has been suggested that this is because `-ix' and `-ex' are Latin singular endings that attract a Latinate plural. Finally, it has been suggested to general approval that the plural of `mongoose' ought to be `polygoose'.

The pattern here, as with other hackish grammatical quirks, is generalization of an inflectional rule that in English is either an import or a fossil (such as the Hebrew plural ending `-im', or the Anglo-Saxon plural suffix `-en') to cases where it isn't normally considered to apply.

This is not `poor grammar', as hackers are generally quite well aware of what they are doing when they distort the language. It is grammatical creativity, a form of playfulness. It is done not to impress but to amuse, and never at the expense of clarity.

Spoken Inarticulations

Words such as `mumble', `sigh', and `groan' are spoken in places where their referent might more naturally be used. It has been suggested that this usage derives from the impossibility of representing such noises in electronic mail. Interestingly, the same sorts of constructions have been showing up with increasing frequency in comic strips. Another expression sometimes heard is 'Complain!' meaning 'I have a complaint!'

Anthropomorphization

Semantically, one rich source of jargon constructions is the hackish tendency to anthropomorphize hardware and software. This isn't done in a naive way; hackers do not believe that the things they work on every day are `alive' but it is common to hear of hardware or software as though it has some creatures talking to each other inside it, with intentions and desires. E.g.: 'The protocol handler got confused', «Programs are trying to do smth», «A routine’s goal in life is to X'. One even hears explanations like '... and its poor little brain couldn't understand X, and it died.'

Anything with a really complex behavioral repertoire is usually thought of as `like a person' rather than `like a thing'. Thus, anthropomorphisation makes sentences easier to understand.

Comparatives

Many words in hacker jargon have to be understood as members of sets of comparatives. This is especially true of the adjectives and nouns used to describe the beauty and functional quality of code. Here is an approximately correct spectrum:

monstrosity

brain-damage

screw

bug

lose

misfeature

crock

kluge

hack

win

feature

elegance

perfection

The last is spoken of as a mythical absolute, approximated but never actually attained.

Another similar scale is used for describing the reliability of software: broken

flaky

dodgy

fragile

brittle

solid

robust

bulletproof

armor-plated

`Dodgy' is primarily Commonwealth Hackish and it is rare in the U.S.A. and may change places with `flaky' for some speakers.

Coinages for describing lossage seem to call forth the very finest in hackish linguistic inventiveness.

It has been truly said that hackers have even more words for equipment failures than Yiddish has for obnoxious people.

Hacker Style

Hacker Speech Style

Hackish speech generally features extremely precise diction, careful word choice, a relatively large working vocabulary, and relatively little use of contractions or street slang. Dry humor, irony, puns, and a mildly flippant attitude are highly valued -- but an underlying seriousness and intelligence are essential. One should use just enough jargon to communicate precisely and identify oneself as a member of the culture; overuse of jargon or a breathless, excessively gung-ho attitude is not respected.

This speech style is a variety of the precisionist English normally spoken by scientists, design engineers, and academics in technical fields. In contrast with the methods of jargon construction, it is fairly constant throughout hackerdom.

It has been observed that many hackers are confused by negative questions - or the people to whom they talk are often confused by the sense of their answers. They have done so much programming that distinguishes between if (going) ... that means «If we are going» and if (!going) ...that means «If we are not going» when they parse the question 'Aren't you going?' it seems to be asking the opposite question from 'Are you going?', and so merits an answer in the opposite sense. This confuses English-speaking non-hackers because they were taught to answer as though the negative part weren't there. In some other languages (including Russian, Chinese, and Japanese) the hackish interpretation is standard and the problem wouldn't arise. Hackers often find themselves wishing for a word like French `si' or German `doch' with which one could unambiguously answer `yes' to a negative question.

For similar reasons, English-speaking hackers almost never use double negatives, even if they live in a region where colloquial usage allows them. The thought of uttering something that logically ought to be an affirmative knowing it will be misparsed as a negative tends to disturb them.

In a related vein, hackers sometimes make a game of answering questions containing logical connectives with a strictly literal rather than colloquial interpretation. A non-hacker who is indelicate enough to ask a question like 'So, are you working on finding that bug now or leaving it until later?' is likely to get the perfectly correct answer 'Yes!' (that is, 'Yes, I'm doing it either now or later, and you didn't ask which!').

Hacker Writing Style

As it has been said, hackers often coin jargon by generalizing grammatical rules. This is one aspect of a more general fondness for form-versus-content language jokes that shows up particularly in hackish writing. Hackers claim that many people have been known to criticize hacker jargon by observing: «This sentence no verb», or «Too repetetetive», or «Bad speling», or «Incorrectspa cing.»

Similarly, intentional spoonerisms are often made of phrases relating to confusion or things that are confusing; `dain bramage’ for `brain damage’ is perhaps the most common (similarly, a hacker would be likely to write «Excuse me, I’m cixelsyd today», rather than «I’m dyslexic today»). This sort of thing is quite common and is enjoyed by all concerned.

Hackers tend to use quotes as balanced delimiters like parentheses, much to the dismay of American editors. Thus, if «Jim is going» is a phrase, and so are «Bill runs» and «Spock groks», then hackers generally prefer to write: «Jim is going», «Bill runs», and «Spock groks». This is incorrect according to Standard American usage (which would put the continuation commas and the final period inside the string quotes).

Hackers tend to distinguish between `scare’ quotes and `speech’ quotes; that is, to use British-style single quotes for marking and reserve American-style double quotes for actual reports of speech or text included from elsewhere. Interestingly, some authorities describe this as correct general usage.

One further not standard permutation is a hackish tendency to do marking quotes by using apostrophes (single quotes) in pairs; that is, ‘like this’.

In the E-mail style of UNIX hackers in particular there is a tendency for usernames and the names of commands and C routines to remain uncapitalized even when they occur at the beginning of sentences. For many hackers, the case of such identifiers becomes a part of their internal representation (the `spelling’).

Behind these nonstandard hackerisms there is a rule that precision of expression is more important than conformance to traditional rules; where the latter create ambiguity or lossage of information. It is notable in this respect that other hackish inventions in vocabulary tend to carry very precise shades of meaning even when constructed to appear slangy and loose.

Hackers have also developed a number of punctuation and emphasis conventions.

One of these is that TEXT IN ALL CAPS IS INTERPRETED AS `LOUD’, a person that writes in this way may be asked to «stop shouting, please, you’re hurting my ears!»

Also, it is common to use bracketing with unusual characters to signify emphasis. The asterisk is the most common, even though this interferes with the common use of the asterisk as a footnote mark.

E.g.: «What the hell?»

The underscore is also common, suggesting underlining. This is particularly common with book titles.

E.g.: «It is often alleged that Joe Haldeman wrote TheForeverWar as a rebuttal to Robert Heinlein’s earlier novel of the future military, StarshipTroopers.».

Other forms exemplified by «=hell=», «hell/», or «/hell/» are occasionally seen. Some hackers claim that «in the last example the first slash pushes the letters over to the right to make them italic, and the second keeps them from falling over».

Finally, words may also be emphasized L I K E T H I S, or by a series of carets (^) under them on the next line of the text.

There is a semantic difference between emphasis LIKE THIS(which emphasizes the phrase as a whole), and emphasis L I K E T H I S (which suggests the writer speaking very slowly and distinctly, as if to a very young child or a mentally impaired person). Bracketing a word with the `’ character may also indicate that the writer wishes readers to consider that an action is taking place or that a sound is being made.

E.g.: `bang’, `ring’, `mumble’.

There is also an accepted convention for `writing under erasure’; the text «Be nice to this fool^H^H^H^Hgentleman, he’s visiting from corporate HQ.» may be interpreted as «Be nice to this fool, er, gentleman...»

Crackers, phone phreaks, and warez d00dz (mostly teenagers running PC-clones from their bedrooms) have developed their own characteristic jargon, heavily influenced by skateboard lingo and underground-rock slang.

Here is a brief guide to cracker and warez d00dz usage:

Misspell frequently. The substitutions

phone => fone

freak => phreak are obligatory.

Always substitute `z's for `s's. (i.e. 'codes' -> 'codez').

Type random emphasis characters after a post line (i.e. 'Hey Dudes!#!$#$!#!$').

Use the emphatic `k' prefix ('k-kool', 'k-rad', 'k-awesome') frequently.

Abbreviate compulsively ('I got lotsa warez w/ docs').

Substitute `0' for `o' ('r0dent', 'l0zer').

TYPE ALL IN CAPS LOCK, SO IT LOOKS LIKE YOU'RE YELLING ALL THE TIME.

`*’ signifies multiplication but two asterisks in a row are a shorthand for exponentiation (this derives from FORTRAN). Thus, one might write 2 ** 8 = 256.

Another notation for exponentiation one sees more frequently uses the caret (^, ASCII 1011110); one might write instead `2^8 = 256’.

In on-line exchanges, hackers tend to use decimal forms or improper fractions (`3.5’ or `7/2’) rather than `typewriter style’ mixed fractions (`3-1/2’). The major motive here is probably that the former are more readable, together with a desire to avoid the risk that the latter might be read as `three minus one-half’. The decimal form is definitely preferred for fractions with a terminating decimal representation; there may be some cultural influence here from the high status of scientific notation.

Another on-line convention, used especially for very large or very small numbers, is taken from C (which derived it from FORTRAN). This is a form of `scientific notation’ using `e’ to replace `*10^’; for example, one year is about 3e7 seconds long.

The tilde (~) is commonly used in a quantifying sense of `approximately’; that is, `~50’ means `about fifty’.

On USENET common logical and relational operators such as `|’, `&’, `||’, `&&’, `!’, `’, `!=’, `>’, `<’, `>=’, and `=<’ are often combined with English. The use of prefix `!’ as a loose synonym for `not-‘ or `no-‘ is particularly common; thus, `!clue’ is read `no-clue’ or `clueless’.

A related practice borrows syntax from preferr oday’s net volumes? #endif /* FLAME */ I guess they figured the price premium for true frame-based semantic analysis was too high. Unfortunately, it’s also the only workable approach. I wouldn’t recommend purchase of this product unless you’re on a very tight budget. #include -- Frank Foonly (Fubarco Systems)

tight budget. #include -- Frank Foonly (Fubarco Systems) In the above, the `#ifdef’ / `#endif’ pair is a conditional compilation syntax from C; here, it implies that the text between (which is a Îøèáêà! Çàêëàäêà íå îïðåäåëåíà.) should be evaluated only if you have turned on (or defined on) the switch FLAME. The `#include’ at the end is C for «include standard disclaimer here»; the `standard disclaimer’ is understood to read, roughly, «These are my personal opinions and not to be construed as the official position of my employer.»

The top section in the example, with > at the left margin, is an example of an inclusion convention we’ll discuss below.

Hackers also mix letters and numbers more freely than in mainstream usage. In particular, it is good hackish style to write a digit sequence where you intend the reader to understand the text string that names that number in English. So, hackers prefer to write `1970s’ rather than `nineteen-seventies’ or `1970’s’ (the latter looks like a possessive).

It should also be noted that hackers exhibit much less reluctance to use multiply nested parentheses than is normal in English. Part of this is almost certainly due to influence from LISP (which uses deeply nested parentheses (like this (see?)) in its syntax a lot), but it has also been suggested that a more basic hacker trait of enjoying playing with complexity and pushing systems to their limits is in operation.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that many studies of on-line communication have shown that electronic links have a de-inhibiting effect on people. Deprived of the body-language cues through which emotional state is expressed, people tend to forget everything about other parties except what is presented over that ASCII link. This has both good and bad effects. A good one is that it encourages honesty and tends to break down hierarchical authority relationships; a bad one is that it may encourage depersonalization and gratuitous rudeness. Perhaps in response to this, experienced netters often display a sort of conscious formal politesse in their writing that has passed out of fashion in other spoken and written media (for example, the phrase «Well said, sir!» is not uncommon).

Many introverted hackers who are next to inarticulate in person communicate with considerable fluency over the net, perhaps precisely because they can forget on an unconscious level that they are dealing with people and thus don’t feel stressed and anxious as they would face to face.

Though it is considered gauche to publicly criticize posters for poor spelling or grammar, the network places a premium on literacy and clarity of expression. It may well be that future historians of literature will see in it a revival of the great tradition of personal letters as art.

International Style

Though the hacker-speak of other languages often uses translations of jargon from English, the local variations are interesting, and knowledge of them may be of some use to travelling hackers.

There are some variations in hacker usage as reported in the English spoken in Great Britain and the Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, India, etc. -- though Canada is heavily influenced by American usage). Commonwealth hackers are more likely to pronounce transactions like «char» and «soc», etc., as spelled /char/, /sok/, as opposed to American /keir/ and /sohsh/. Dots in newsgroup names (especially two-component names tend to be pronounced more often.

E.g.: soc.wibble is /sok dot wib’l/ rather than /sohsh wib’l/.

The prefix meta may be pronounced /mee’t*/; similarly, Greek letter is usually /bee’t*/, zeta is usually /zee’t*/, and so forth. Preferred metasyntactic variables include ‘eek’, ‘ook’, ‘frodo’, and ‘bilbo’; ‘wibble’, ‘wobble’, and in emergencies ‘wubble’, ‘flob’, etc.

Alternatives to verb doubling include suffixes ‘-o-rama’, ‘frenzy’, and ‘city’.

E.g.: «hack-o-rama!», «core dump frenzy!», «barf city!’

Finally, the American terms for «parenthesis», «brackets», and «braces» for (), [], and {} are uncommon. Commonwealth hackish prefers «brackets», «square brackets», and «curly brackets».

Hackers in Western Europe and (especially) Scandinavia report that they often use a mixture of English and their native languages for technical conversation. Occasionally they develop idioms in their English usage that are influenced by their native-language styles. Some of these are reported here.

Hacker Humour

A distinctive style of shared intellectual humor found among hackers has the following marked characteristics:

1. Fascination with form-vs.-content jokes, paradoxes, and humor having to do with confusion of. A metasyntactic variable is a variable in notation used to describe syntax, and meta-language is language used to describe language.

Metasyntactic variable is a name used in examples and understood to stand for whatever thing is under discussion, or any random member of a class of things under discussion. The word foo is the canonical example. To avoid confusion, hackers never use `foo' or other words like it as permanent names for anything. In filenames, a common convention is that any filename beginning with a metasyntactic-variable name is a scratch file that may be deleted at any time.

To some extent, the list of one's preferred metasyntactic variables is a cultural signature. They occur both in series and as singletons. Here are a few common signatures:

foo, bar, baz, quux, quuux, quuuux...:

Some jargon terms are also used as metasyntactic names; barf and mumble, for example.

2. Elaborate deadpan parodies of large intellectual constructs, such as standards documents, language descriptions (see Îøèáêà! Çàêëàäêà íå îïðåäåëåíà.), and even entire scientific theories, for instance, Îøèáêà! Çàêëàäêà íå îïðåäåëåíà., Îøèáêà! Çàêëàäêà íå îïðåäåëåíà.).

3. Fascination with puns and wordplay.

Pronunciation Features

Pronunciation keys provided in the Glossary of Terms are not dictionary words pronounced as in standard. Slashes bracket phonetic pronunciations, which are to be interpreted using the following conventions:

1. Syllables are hyphen-separated, except that an accent or back-accent follows accented syllable (the back-accent marks a secondary accent in some words of four or more syllables). If no accent is given, the word is pronounced with equal accentuation on all syllables (this is common for abbreviations).

1. Consonants are pronounced as in standard English:

· `g' is always hard (as in 'got' rather than 'giant');

· terminal `r’ (as in «hard» or «more») may be pronounced or not depending on the local dialect

· `j' is the sound that occurs twice in 'judge';

· `s' is always as in 'pass', never a z sound;

· the diagraph `ch' is soft (as in 'church' rather than 'chemist');

· the digraph `kh' is the guttural of 'loch' or 'l'chaim';

· the digraph 'gh' is the aspirated g+h of 'bughouse' or 'ragheap' (this case is rare in English).

2. Uppercase letters are pronounced as their English letter names; E.g.: /H-L-L/ is equivalent to /aych el el/.

/Z/ may be pronounced /zee/ or /zed/ depending on the local dialect.

4. Vowels are represented as follows:

/a/

back, that

/ah/

father, palm

/ar/ or /a:/

far, mark

/aw/

flaw, caught

/ay/

bake, rain

/e/

less, men

/ee/

easy, ski

/eir/ or /ea/

their, software

/i/

trip, hit

/ai/

life, sky

/o/

block, stock (see note)

/oh/

flow, sew

/oo/

loot, through

/or/ or /o:/

more, door

/ow/

out, how

/oy/

boy, coin

/uh/

but, some

/u/

put, foot

/y/

yet, young

/yoo/

few, chew

The glyph /*/ is used for the `schwa' sound of unstressed or occluded vowels (the one that is often written with an upside-down `e'). The schwa vowel is omitted in syllables containing vocalic r, l, m or n; that is, `kitten' and `color' would be rendered /kit'n/ and /kuhl'r/, not /kit'*n/ and /kuhl'*r/.

The above table reflects mainly distinctions found in Standard English (that is, the neutral dialect spoken by TV network announcers and typical of educated speech). Speakers of British Received Pronunciation can smash terminal /r/ and all unstressed vowels. Speakers of many varieties of southern American will automatically change /o/ to /aw/ or /ah/, etc. Entries with a pronunciation of `//' are written-only usages.

Conclusions

Computerization, hacker culture, and hacker jargon are viewed here as a source of lexical, semantic-stylistic, and phonetic changes it introduces into Modern English.

Further investigation of the hacker culture influencing Modern English from the perspective

Bibliography

1. Амосова Н.Н. Английская контекстология. Л., 1968. – 126с.

2. Арнольд И.В. Стилистика современного английского языка. М., Высшая школа, 1973. – 301с.

3. Гальперин И.Р. Очерки по стилистике английского языка. М.: Библиотека филолога, 1958. –458с.

4. Гинзбург Р.З., Хидекель С.С., Князева Г.Ю. и Санкин А.А. Лексикология английского языка. – 2-е изд., испр. и доп. – М.: Высшая школа,1979. – 269с.

5. Каращук П.М. Словообразование английского языка. М., 1965.

6. Кубрякова Е.С. Что такое словообразование. М., 1965.

7. Мешков О.Д. Словообразование современного английского языка. М., 1972.

8. Мостовий М.І. Лексикологія англійської мови. Х.: Основа, 1993. – 256с.

9. Раєвська Н.М. Лексикологія англійської мови

10. Швейцар А.Д. Литературный английский язик в США и Англии. М., 1971.

Îøèáêà! Çàêëàäêà íå îïðåäåëåíà..

Îøèáêà! Çàêëàäêà íå îïðåäåëåíà.

Compilers: Raphael Finkel (1975), In 1976, Mark Crispin (1976), Mark Crispin and Guy L. Steele Jr. (1981), Charles Spurgeon, Raphael Finkel, Don Woods, Mark Crispin, Richard M. Stallman, and Geoff Goodfellow.

Glossary of Terms

= A =

AI /A-I/ /n./ Abbreviation for `Artificial Intelligence', so common that the full form is almost never written or spoken among hackers.

AI-complete /A-I k*m-pleet'/ /adj./ [MIT, Stanford: by analogy with `NP-complete' (see NP-)] Used to describe problems or subproblems in AI, to indicate that the solution presupposes a solution to the `strong AI problem' (that is, the synthesis of a human-level intelligence). A problem that is AI-complete is, in other words, just too hard. Examples of AI-complete problems are `The Vision Problem' (building a system that can see as well as a human) and `The Natural Language Problem' (building a system that can understand and speak a natural language as well as a human).

AI koans /A-I koh'anz/ /pl.n./

A series of pastiches of Zen teaching riddles created by Danny Hillis at the MIT AI Lab around various major figures of the Lab's culture

ASCII /as'kee/ /n./ [acronym: American Standard Code for Information Interchange] The predominant character set encoding of present-day computers.

ASCII art /n./

The fine art of drawing diagrams using the ASCII character set (mainly `|', `-', `/', `', and `+').

ASCIIbetical order /as'kee-be'-t*-kl or'dr/ /adj.,n./ Used to indicate that data is sorted in ASCII collated order rather than alphabetical order.

= B =

backbone site /n./ A key Usenet and email site; one that processes a large amount of third-party traffic, especially if it is the home site of any of the regional coordinators for the Usenet maps.

BAD /B-A-D/ /adj./ [IBM: acronym, `Broken As Designed'] Said of a program that is bogus because of bad design and misfeatures rather than because of bugginess.

bagbiter /bag'bi:t-*r/ /n./

1. a program or a computer, that fails to work, or works in a remarkably clumsy manner.

E.g.:'This text editor won't let me make a file with a line longer than 80 characters! What a bagbiter!'

2. A person who has caused you some trouble, inadvertently or otherwise, typically by failing to program the computer properly.

Syn.: loser, cretin, chomper.

3. `bite the bag' /vi./ To fail in some manner. 'The computer keeps crashing every five minutes.' 'Yes, the disk controller is really biting the bag.' The original loading of these terms was almost undoubtedly obscene, possibly referring to the scrotum, but in their current usage they have become almost completely sanitized.

ITS's `lexiphage' program was the first and to date only known example of a program intended to be a bagbiter.

bagbiting /adj./ Having the quality of a bagbiter. 'This bagbiting system won't let me compute the factorial of a negative number.'

Bang

1. /n./ Common spoken name for `!' /interj./ An exclamation signifying roughly 'I have achieved enlightenment!', or 'The dynamite has cleared out my brain!'

barf /barf/ or /ba:f/ /n.,v./ [from mainstream slang meaning `vomit']

1. /interj./ Term of disgust.

2. /vi./ to express disgust.

E.g.: 'I showed him my latest hack and he barfed' means only that he complained about it, not that he literally vomited.

3. /vi./ To fail to work because of unacceptable input, perhaps with a suitable error message, perhaps not.

E.g.: 'The division operation barfs if you try to divide by 0.' means that the division operation checks for an attempt to divide by zero, and if one is encountered it causes the operation to fail in some unspecified, but generally obvious, manner.

Syn.: choke, gag.

In Commonwealth Hackish, `barf' is generally replaced by `puke' or `vom'.

barfulation /bar`fyoo-lay'sh*n/ /interj./

Variation of barf used around the Stanford area. An exclamation, expressing disgust. On seeing some particularly bad code one might exclaim, 'Barfulation! Who wrote this, Quux?'

barfulous /bar'fyoo-l*s/ /adj./

(alt. `barfucious', /bar-fyoo-sh*s/)

Said of something that would make anyone barf, if only for esthetic reasons.

BASIC /bay'-sic/ /n./ [acronym: Beginner's All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code] A programming language, originally designed for Dartmouth's experimental timesharing system in the early 1960s, which has since become the leading cause of brain damage in proto-hackers. Edsger W. Dijkstra observed in 'Selected Writings on Computing: A Personal Perspective' that 'It is practically impossible to teach good programming style to students that have had prior exposure to BASIC: as potential programmers they are mentally mutilated beyond hope of regeneration.'

This is another case (like Pascal) of the cascading lossage that happens when a language deliberately designed as an educational toy gets taken too seriously. A novice can write short BASIC programs (on the order of 10-20 lines) very easily; writing anything longer (a) is very painful, and (b) encourages bad habits that will make it harder to use more powerful languages well. This wouldn't be so bad if historical accidents hadn't made BASIC so common on low-end micros. As it is, it ruins thousands of potential wizards a year.

[1995: Some languages called `BASIC' aren't quite this nasty any more, having acquired Pascal- and C-like procedures and control structures and shed their line numbers. --ESR]

BiCapitalization /n./

The act said to have been performed on trademarks (such as PostScript, NeXT, NeWS, VisiCalc, FrameMaker, TK!solver, EasyWriter) that have been raised above the ruck of common coinage by nonstandard capitalization..

big win /n./

Serendipity. 'Yes, those two physicists discovered high-temperature superconductivity in a batch of ceramic that had been prepared incorrectly according to their experimental schedule. Small mistake; big win!' See win big.

bigot /n./ A person who is religiously attached to a particular computer, language, operating system, editor, or other tool (see religious issues). Usually found with a specifier; thus, `cray bigot', `ITS bigot', `APL bigot', `VMS bigot', `Berkeley bigot'. Real bigots can be distinguished from mere partisans or zealots by the fact that they refuse to learn alternatives even when the march of time and/or technology is threatening to obsolete the favored tool. It is truly said 'You can tell a bigot, but you can't tell him much.'

bits /pl.n./

1. Information. Examples: 'I need some bits about file formats.' ('I need to

know about file formats.') Compare core dump, sense 4. 2. Machine-readable representation of a document, specifically as contrast ally, the opposite of `real computer' (see Get a real computer!). See also mess-dos, toaster, and toy.

Blue box

/n./ 1. obs. Before all-digital switches made it possible for the phone companies to move them out of band, one could actually hear the switching tones used to route long-distance calls. Early phreakers built devices called `blue boxes' that could reproduce these tones, which could be used to commandeer portions of the phone network.

= C =

C /n./

1. The name of a programming language designed by Dennis Ritchie during the early 1970s and immediately used to reimplement Unix; so called because many features derived from an earlier compiler named `B' in commemoration of its parent, BCPL.

= D =

dark-side hacker /n./ A criminal or malicious hacker; a cracker. From George Lucas's Darth Vader, 'seduced by the dark side of the Force'.

Ant. samurai.

dead /adj./

1. Non-functional; down; crashed. Especially used of hardware.

2. Useless; inaccessible.

Ant.: `live'.

dead code /n./

Routines that can never be accessed because all calls to them have been removed, or code that cannot be reached because it is guarded by a control structure that provably must always transfer control somewhere else. The presence of dead code may reveal either logical errors due to alterations in the program or significant changes in the assumptions and environment of the program

Syn. grunge.

deadlock /n./

1. [techspeak] A situation wherein two or more processes are unable to proceed because each is waiting for one of the others to do something.

Also used of deadlock-like interactions between humans.

Same as deadlock, though usually used only when exactly two processes are involved. This is the more popular term in Europe, while deadlock predominates in the United States.

= E =

elegant /adj./ [from mathematical usage] Combining simplicity, power, and a certain ineffable grace of design. Higher praise than `clever', `winning', or even cuspy.

elite /adj./ Clueful. Plugged-in. One of the cognoscenti. Also used as a general positive adjective. This term is not actually hacker slang in the strict sense; it is used primarily by crackers and warez d00dz. Cracker usage is probably related to a 19200cps modem called the `Courier Elite' that was widely popular on pirate elder days.

email /ee'mayl/ (also written `e-mail' and `E-mail') 1. /n./ Electronic mail automatically passed through computer networks and/or via modems over common-carrier lines. Contrast snail-mail, paper-net, voice-net. See etwork

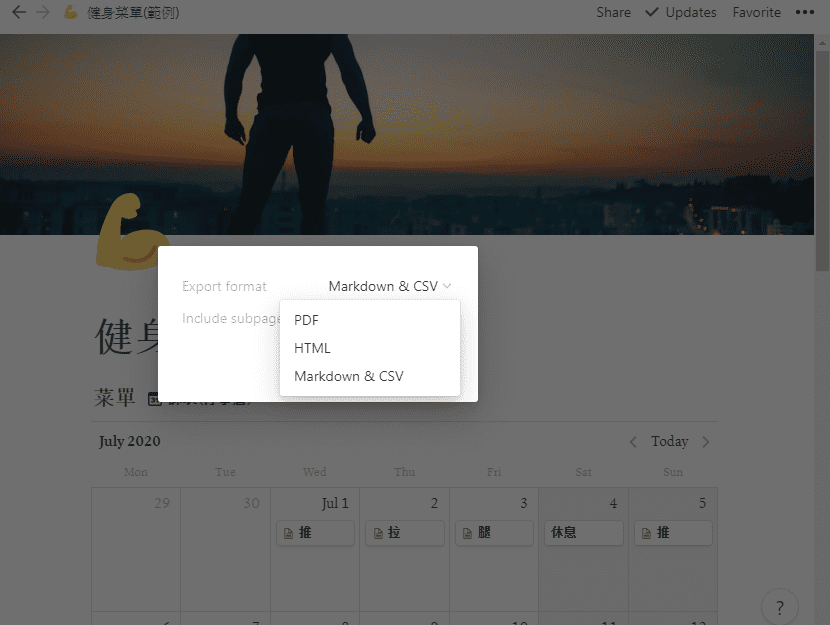

Notion To Markdown Pdf

address. 2. /vt./ To send electronic mail. Oddly enough, the word `emailed' is actually listed in the OED; it means 'embossed (with a raised pattern) or perh. arranged in a net or open work'. A use from 1480 is given. The word is probably derived from French `'emaill'e' (enameled) and related to Old French `emmaille'ure' (network). A French correspondent tells us that in modern French, `email' is a hard enamel obtained by heating special paints in a furnace; an `emailleur' (no final e) is a craftsman who makes email (he generally paints some objects (like, say, jewelry) and cooks them in a furnace).

There are numerous spelling variants of this word. In Internet traffic up to 1995, `email' predominates, `e-mail' runs a not-too-distant second, and `E-mail' and `Email' are a distant third and fourth.

= G =

gen /jen/ /n.,v./ Short for generate, used frequently in both spoken and written contexts.

generate /vt./ To produce something according to an algorithm or program or set of rules, or as a (possibly unintended) side effect of the execution of an algorithm or program.

Ant. parse.

Gosperism /gos'p*r-izm/ /n./ A hack, invention, or saying due to arch-hacker R. William (Bill) Gosper. Many of the entries in HAKMEM are Gosperisms.

grilf // /n./

Girlfriend. Like newsfroup and filk, a typo reincarnated as a new word. Seems to

have originated sometime in 1992 on Usenet.

= H =

Hack

1. /n./ Originally, a quick job that produces what is needed, but not well.

2. /n./ An incredibly good, and perhaps very time-consuming, piece of work that produces exactly what is needed.

3. /vt./ To bear emotionally or physically. 'I can't hack this heat!'

4. /vt./ To work on something (typically a program).

E.g.: 'What are you doing?' 'I'm hacking TECO.'

5. /vi./ To interact with a computer in a playful and exploratory rather than goal-directed way.

E.g.:'Whatcha up to?' 'Oh, just hacking.'

6. /n./ Short for hacker.

`happy hacking' (a farewell), `how's hacking?' (a friendly greeting among hackers) and `hack, hack' (a fairly content-free but friendly comment, often used as a temporary farewell).

hack mode /n./

1. What one is in when hacking.

Export Notion Markdown

2. More specifically, a Zen-like state of total focus on The Problem that may be achieved when one is hacking (this is why every good hacker is part mystic). Ability to enter such concentration at will correlates strongly with wizardliness; it is one of the most important skills learned during larval stage. Sometimes amplified as `deep hack mode'.

hack on /vt./ To hack; implies that the subject is some pre-existing hunk of code that one is evolving, as opposed to something one might hack up.

hack together /vt./ To throw something together so it will work. Unlike `kluge together' or cruft together, this does not necessarily have negative connotations.

hack up /vt./ To hack, but generally implies that the result is a hack in sense 1 (a quick hack). Contrast this with hack on. To `hack up on' implies a quick-and-dirty modification to an existing system. Contrast hacked up; compare kluge up, monkey up, cruft together.

hack value /n./ Often adduced as the reason or motivation for expending effort toward a seemingly useless goal, the point being that the accomplished goal is a hack.

For example, MacLISP had features for reading and printing Roman numerals, which were installed purely for hack value. See display hack for one method of computing hack value, but this cannot really be explained, only experienced. As Louis Armstrong once said when asked to explain jazz: 'Man, if you gotta ask you'll never know.' (Feminists please note Fats Waller's explanation of rhythm:

'Lady, if you got to ask, you ain't got it.')

hacker /n./ [originally, someone who makes furniture with an axe]

1. A person who enjoys exploring the details of programmable systems and how to stretch their capabilities, as opposed to most users, who prefer to learn only the minimum necessary.

2. One who programs enthusiastically (even obsessively) or who enjoys programming rather than just theorizing about programming.

3. A person capable of appreciating hack value.

4. A person who is good at programming quickly.

5. An expert at a particular program, or one who frequently does work using it or on it; as in `a Unix hacker'.

6. An expert or enthusiast of any kind. One might be an astronomy hacker, for example.

7. One who enjoys the intellectual challenge of creatively overcoming or circumventing limitations.

8. [deprecated] A malicious meddler who tries to discover sensitive information by poking around. Hence `password hacker', `network hacker'. The correct term for this sense is cracker.

The term `hacker' also tends to connote membership in the global community defined by the net (see network, the and Internet address). It also implies that the person described is seen to subscribe to some version of the hacker ethic (see hacker ethic).

It is better to be described as a hacker by others than to describe oneself that way. Hackers consider themselves something of an elite (a meritocracy based on ability), though one to which new members are gladly welcome. There is thus a certain ego satisfaction to be had in identifying yourself as a hacker (but if you claim to be one and are not, you'll quickly be labeled bogus).

hacker ethic /n./

1. The belief that information-sharing is a powerful positive good, and that it is an ethical duty of hackers to share their expertise by writing free software and facilitating access to information and to computing resources wherever possible.

2. The belief that system-cracking for fun and exploration is ethically OK as long as the cracker commits no theft, vandalism, or breach of confidentiality.

hacker humor A distinctive style of shared intellectual humor found among hackers.

hacking run /n./ A hack session extended long outside normal working times, especially one longer than 12 hours.

Hacking X for Y /n./ [ITS] Ritual phrasing of part of the information which ITS made publicly available about each user. This information (the INQUIR record) was a sort of form in which the user could fill out various fields. On display, two of these fields were always combined into a project description of the form 'Hacking X for Y' (e.g., 'Hacking perceptrons for Minsky'). This form of description became traditional and has since been carried over to other systems with more general facilities for self-advertisement.

Hackintosh /n./ 1. An Apple Lisa that has been hacked into emulating a Macintosh (also called a `Mac XL'). 2. A Macintosh assembled from parts theoretically belonging to different models in the line.

hackish /hak'ish/ /adj./ (also hackishness n.) 1. Said of something that is or involves a hack. 2. Of or pertaining to hackers or the hacker subculture.

hackishness /n./

The quality of being or involving a hack. This term is considered mildly silly.

Syn. hackitude.

hackitude /n./

Syn. hackishness; this word is considered sillier.

HAKMEM /hak'mem/ /n./ A 6-letterism for `hacks memo'A legendary collection of neat mathematical and programming hacks contributed by many people at MIT and elsewhere.

hakspek /hak'speek/ /n./ A shorthand method of spelling found on many British academic bulletin boards and talker systems. Syllables and whole words in a sentence are replaced by single ASCII characters the names of which are phonetically similar or equivalent, while multiple letters are usually dropped. Hence, `for' becomes `4'; `two', `too', and `to' become `2'; `ck' becomes `k'. 'Before I see you tomorrow' becomes 'b4 i c u 2moro'. First appeared in London about 1986, and was probably caused by the slowness of available talker systems, which operated on archaic machines with outdated operating systems and no standard methods of communication. Has become rarer since. See also talk mode.

hand-hacking /n./

1. The practice of translating hot spots from an HLL into hand-tuned assembler, as opposed to trying to coerce the compiler into generating better code. Both the term and the practice are becoming uncommon. See tune, bum, by hand; syn. with /v./ cruft.

2. More generally, manual construction or patching of data sets that would normally be generated by a translation utility and interpreted by another program, and aren't really designed to be read or modified by humans.

haque /hak/ /n./

[Usenet] Variant spelling of hack, used only for the noun form and connoting an elegant hack.

hardwarily /hard-weir'*-lee/ /adv./

In a way pertaining to hardware. E.g.:'The system is hardwarily unreliable.' The adjective `hardwary' is not traditionally used.

HLL /H-L-L/ /n./ [High-Level Language] Found primarily in email and news rather than speech. Rarely, the variants `VHLL' and `MLL' are found. VHLLstands for `Very-High-Level Language' and is used to describe Standard English that the speaker happens to like; Prolog and

Backus's FP are often called VHLLs. `MLL' stands for `Medium-Level Language' and is som

Notion Markdown 支持